Standing amazed by the splendour of quincentennial Bagha Shahi Masjid, I recalled a 2017 incident in Philadelphia, U.S.

It was an early September morning, and we were on a study trip to Independence National Historical Park. The excited lecturer of ‘American Studies’ was describing the antiquity and significance of the Philadelphia Liberty Bell. It is a 935 kg and 266 years’ old simple-looking metal bell, which was commissioned in 1751 by the colonial legislative assembly of Pennsylvania. It was occasionally used to call lawmakers or prior to making public announcements until 1835, after which, following a permanent crack developed on it, the bell was never used. The bell and its crack gained prominence over the years by extensive publicity and symbolism.

Our presenter was laying so much emphasis on the bell (and its crack) that one of us could not help but ask: What would you do if you have places with thousand years of relics and traditions?

: I would make a lot of money out of it. He smiled and replied.

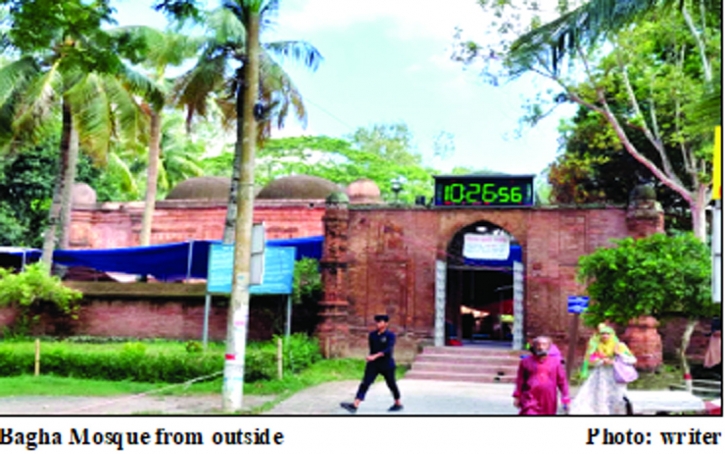

The gentleman might have sounded a bit materialistic; but the point made was important: history and traditions are attractive to the point that people are ready to spend money and time after them. This could be due to our natural bias to trace back our ‘roots’ of origin, our ancestry. This could even be about finding answers to one of those longstanding innate existential questions. After recently visiting Bagha Shahi Masjid, which has reached its five hundred years this year, I wondered, could it be presented better to bring alive the old days? Bagha, a small Upazila located on the north-western ‘shoulder’ of Bangladesh, was a thriving trading centre and an education hub during the medieval ages. In 1609, Abd al Latif, a Mughal royal official was traveling from Agra to Bengal. He was in fact accompanying Mughal Subahdar Islam Khan in their journey by river from Raajmahal to Ghoraghat. On the way, Abd al Latif visited the Bagha madrasah, where he met an elderly Sufi named Hawadah Miah. He wrote in his Safarnama about the serene environment where the elderly man was running a madrasah and a khanqah in such a remote place. Hawadah Mian’s real name was Maulana Hamid Danishmand, who was the son of Shah Muazzam Danishmand alias Maulana Shah Daula. Shah Muazzam Danishmand came from Baghdad and settled there during the reign of the Sultan of Bengal Nasiruddin Nasrat Shah (1519– 32). He was given 42 parganas as imperial grant and built his khanqah there. Legend holds that he could tame the wandering wild tigers (Bagh) of the area and set up a habitat. The name of the area Bagha traces back to this legend.

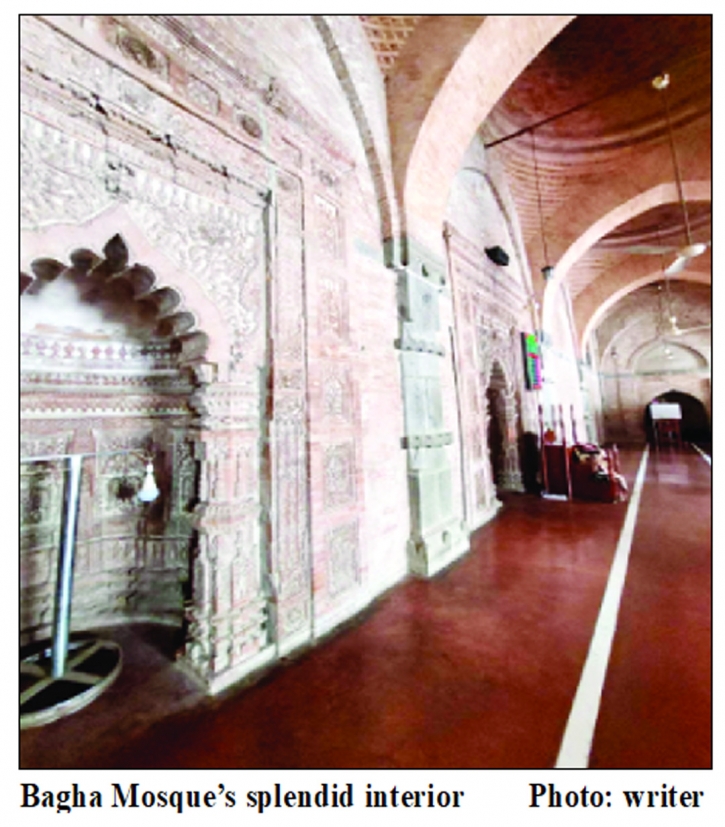

The inscription that attested the history and heritage of the famous mosque, was transferred to some museum in Karachi before the independence of Bangladesh. The writing was captured and translated by eminent historian Dr Abdul Karim: ‘This Jami mosque was built during the reign of the exalted sultan son of the Sultan, Nasir al dunia Wal din Abul Muzaffar Nusrat Sha, the sultan son of Husain Sha the Sultan .’ The magnificently ornate rectangular mosque with four decorated corner towers was constructed on an about 10 feet high stone-base. It is a formidable structure with an area of 3150 square feet (75 feet long and 42 feet wide) and a height of 24 feet. We have to consider the difficulties involved in those days in not only finding craftsmen, but also the non-availability of such material nearby, thus needing them to be transported maybe from far western stone-rich areas. The mosque has five brilliantly decorated archways entrances. There are ten semicircular domes on the arched roof supported by six pillars made of black basalt stone. The bricks used are uniquely crafted, each measuring ten-inch in length, six inches in width and one and a half inches thick. There is a nearby smaller three domed structure too, which was a worshipping place for the females. Even with so much of technological and conveyance progress, we hardly see such superb making in modern days.

During the earthquake of 1897, a part of the mosque collapsed. That was repaired later in accordance with the actual design. Many of the decorated terracotta tiles have been broken and a lot of the beautiful patterns are damaged. Yet whatever remains today, are good enough to take the visitors on a time-travel to a few centuries back. The huge water tank (Dighi) beside the mosque was made definitely with the purpose of community building and community expansion. Abd al Latif’s Safarnama also substantiates this assumption. Drinking water was something the people needed badly, and they mostly relied on the rivers and ponds. The astonishingly big sized tank (occupying 52 bighas of land), surrounded by coconut and other trees must have been a good source of fresh water that attracted local people, newly converted Muslims. They were certainly delighted in finding a place for living, settling and also educating the children. Richard M. Eaton in his The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760 argues how the Muslim Sufis and Saints contributed immensely in the expansion of economic opportunity and community-building of Bengal. Around the time when Bagha masjid was established, it was a whole jungle infested by tigers, elephants, rhinos etc. Mirza Nathan, a Mughal naval commander, traveling along the same route like Latif for his naval expedition against the Baro Bhuians, mentions vividly (in his book Baharistan I Gaibi), about hunting and making a Khedda(stockade trap for hunting the full herd of elephant) in nearby places . Alaipur, just three miles away from Bagha, was a well-known place that rose to prominence in the sixteenth century and during Mughal rule.

It is not easy to visualise a five hundred years’ old locality of Bagha-Alaipur through today’s lenses. For that, we need a setting to be created by sights, sounds and info-graphics. To credibly mind-map the reality of those times, history should be presented attractively and realistically, something that we see at the places like Mount Vernon of Virginia, USA. There, the sculptures of the workers and slaves come alive in the bunks, kitchens, stables, living areas in the house of George Washington. Things are presented exactly they prevailed. There are even real people (like blacksmith) role playing and drawing attention from fascinated crowd and children. We have similar or even greater potentials here in Bangladesh, and we have them in abundance, just the efforts and interests need to be binded with the potentials. After visiting Bagha Shahi Masjid, which has reached its 500th year in 2023, I pondered with great cognizance; it is feasible.